ALYSSA’S SCENT

Alyssa once told me that my paintings were incredible, and at the time, I pretended to be offended, telling her that the only objective I’d ever set for myself in the art world was to be credible. What made that response less cute and more ironic is that Alyssa’s output really was incredible; she was the most intrinsically talented individual I’ve ever met. Across several disciplines, too: She could play guitar as well as she could sing, and as for her paintings, I’d pulled work from her dumpster that was better than anything I’ve sold. She painted from inside the head rather than from inside the business, and as a result, not only did she never sell a single piece, I doubt she’d have taken money for one had it been offered.

Why Alyssa called my work incredible is an accumulation of circumstances, some more poignant than others. I believe I have an obligation to explain them—to explain her, because in the end, I figured her out and not many others did. Perhaps I owe her this, or maybe I owe me.

As to the comment about my artwork, she knew I thrived on flattery and drew creative nutrients from it, and maybe she understood the nuance behind her own semantics. Perhaps she actually did consider my art non-credible, and it was less the paintings she admired than my certainty about its worldly value. In retrospect, that makes sense—for the creative process to evolve, self-belief is axiomatic. Her own confidence was quiet and self-contained; mine was loud and remains so today.

To remember her face in words the way I remember them when I paint, I will describe Alyssa like this: She had the sort of delicacy about her features made make-up a distraction, but she wore it anyway, calling it an occupational hazard; her waitress job paid the bills since art and music didn’t.

To do the same thing with her sound, Alyssa sang in a crystalline contralto that defied her size; she was slight enough that people commented on it and so flat-chested that it was nearly sad. But from that flat chest came monumental phrasing, and when she accompanied herself on a beat-up Gibson Hummingbird—a leftover from a previous boyfriend—she found esoteric chords unnamed in books on music theory. She allowed her fingers to find them independently of those books and named them silly things like ‘Jim’ and ‘Ray’ because she thought those kinds of dolty, monosyllabic white-boy names were hilarious. Likewise, she had an ancient, mangy, runty mutt called ‘Bill’. When I first began stopping by her house—a tiny bungalow on a rural country lane—Bill must have already been two-hundred in dog years. At the time, Alyssa was the vocalist for a rough-looking country band called ‘Big Hats, No Cattle’ made up of regulars from the bar where she worked, and I recall, they did a lot of drunken rehearsing and drunken auditioning but never landed a gig. Her boss at the bar said that he’d have hired them if he had a stage, which was his polite way of saying he was glad he didn’t have a stage.

That’s a cast of her profile and the sound of her voice. More keenly than either, though, I remember how Alyssa smelled. There’s a reason for that—I have perfect pitch for scents. If I put my mind to it, I can conjure up the smell of virtually every place I’ve ever visited and every person with whom I’ve been intimate. It’s a useless skill if ever one was—like an autistic’s ability to count toothpicks—but it’s there nonetheless. Years ago, I went weak when confronted with Alyssa’s scent and I can still elicit it faithfully, at will, from mysterious mind channels, although for reasons that will become obvious, I go out of my way to avoid doing that.

Was I in love with Alyssa? As I understand it, I’ve never been in love with anyone, and certainly, that includes myself. As a stand-alone concept (like ‘God’) I am not convinced that romantic love actually exists. The self-assurance of which I spoke earlier has to do with my persistent and cynical success at figuring out how things work—something that proved true about my clients and patrons and everyone I’ve slept with, including Alyssa. To me, starry-eyed love seems born out of a neediness I never had, and to hear others prattle on about it is like Stevie Wonder listening to a lecture on turquoise. What I have in its stead is outrageous appreciation for people whose abilities defy logic and an outsized need to be around such folks. As a result, I treasured Alyssa on an honest and encapsulating level—a level on which I don’t think she’d ever before been treasured. That went a long way toward explaining the space she gave me—especially with the ring that appeared on my left hand during our ten-year relationship—and I fully exploited it. In those years, I used her relentlessly; I extracted emotional essence and deposited body essence; I called when I felt like it and bristled if something on her end interfered. And yet, without equivocating, I can state that in that time Alyssa made me understand love as a symbol with substance in same the way that the right poet might make Stevie understand the spectrum.

In the wake of it all, I have loads of shame and no regret, and I’ll try to keep this portrait honest. Alyssa and I were of a moment, and that moment is now gone. In my heart, it may be preserved more perfectly than in any portrait, but it is still a vessel rocketing away, beyond the influence of physics, with no chance of returning.

Every descriptive story about someone you knew should contain a passage on how you met, and this one will be no different:

At the time, I was twenty-six and three years into a follow-your-nose corporate climb in engineering management, the same road taken by my piously white-collar father and older brother. After college, I signed on with a prominent automotive supplier, and shortly before I was due my second promotion, the company entered into a multibillion-dollar merger and moved the business offshore; it’s a tax break known as ‘inversion’. Rather than go with them—and much to the horror of my parents—I resigned and decided to spend the following year seeing if I could make headway in a career that appealed to me on a much more carnal, although equally mercenary level: Fine art. I’d watched Sotheby’s auctions and I saw the sort of paintings that were hauling in Monopoly money, and for me, it all seemed like fairly do-able stuff. I correctly surmised that the fortune to be made had to do with prevailing tastes and orchestrated luck, and that moderate talent could be shored up by commercial technique.

So I rented an impersonal space with high ceilings in an old industrial center downtown and set to work constructing canvases, mostly large, up to ten feet in length. I’d done smaller, experimental paintings all throughout high school and college—oil on Masonite, mostly—and had developed the infrastructure, if not the strategy, to make it a vocation. Now that I was in to win, I wanted to make paintings that dominated whatever space they occupied. Little wouldn’t cut it; I wanted to create my own environment.

I’d never worked in gouache before—a medium that can be seen either as industrial-strength watercolor or profoundly sensitive house paint—and when I visited Diamond Artist Supply, my brain remained in engineering mode. I’d already read up on the application’s most prized qualities and I peppered the clerk with minutia about ‘designer’ gouaches; I wanted to know chemical compositions and spec specifics—which brands used dye pigment or extra filler, which were tinted with white and which were made to Munsell system colors. I discombobulated the poor dude; he sincerely wanted to help and offered to call the manufacturers himself to get my answers. He was in the process of writing down my questions when a pretty girl bounced down the aisle in clingy white jeans and a United Unlimited pullover and said, “None of that makes a difference once you start to paint. It’s not about pigment load; it’s about how you jazz with your subject.”

The clerk was grateful for the life-line: “Alyssa does murals,” he said. “She knows more about it than I do.”

I swept my hand over the list of available option. “I’m new to the school. So, Turner, Lukas, LeFranc; one’s as good as the other?”

She shrugged. “DaVinci comes in a bigger tube for the same cost.”

“What if price is no object?”

“Then you should be buying art instead of making it.”

When she laughed, she looked away, as though it was a private joke and she knew in advance I wouldn’t get it. “Maybe so,” I conceded. “Where are your murals?”

“Aw, there’s just the one. At the bar where I work. The owner wanted it done.”

“Of what?”

“Ty Cobb.”

“The psycho ball player?”

“Right.” she snickered. “How can you not love an athlete who beats up his fans? If I had fans, I’d kick the shit out them every chance I got.”

I was sure that somewhere in the wings she had fans, and in that moment, I became one. I found her attractive, and why not? Slightly mangled syntax aside, she had the kind of wire-frame boldness that men like me find appealing. Sometimes, it’s output of self-assurance and sometimes it’s the shrug of someone without much to lose. I guessed the former because she was about my age and still had the unfolding world to gain.

As it happened, I guessed wrong. At the time, I turned back to the clerk while I considered if there was a non-obnoxious way to ask for her phone number.

“Alyssa bought you a reprieve,” I told him. “I’ll trust her experience and take a set of DaVinci.”

I found Alyssa in a stray aisle and made a rather lame offer to call her to let her know how well my attempts at gouache fared. She responded with sardonic courtesy—at least, that’s how I took it: “You understand that if I gave my phone number to every guy who asked for it I wouldn’t have any phone numbers left.”

Rejection worth a smile, and I was not a poor sport in these circumstances: Equally, if every girl I asked had acquiesced, I’d have had more phone numbers than I could call. But it was during that second encounter that I became aggressively conscious of her smell. Because I’d been aroused, I found it appealing beyond what it was; I thought about it on the trip back to the loft. I analyzed what I recalled, because that’s what I do. There were traces of cigarette and maybe alcohol—faint, stale-bar smells that made sense since she claimed to work in one—and they were mingled with a musk that is uniquely if sporadically feminine. I’d have won a bet in Alyssa’s bar by pointing out which girls were ovulating and which weren’t simply by smelling their necks—probably before I was beaten to a pulp by Ty Cobby boyfriends. But it’s biology, not a parlor trick. A woman emits unique pheromones when she is fertile, and I’d learned to identify it. Also, I’d have made another bet that Alyssa washed her hair with floral shampoo—specifically, apple blossom.

In the years to come, Alyssa’s blend of scents became indelibly imprinted on me, flesh and soul. More nuances were added as I got to know her, but on that drive back to the loft I was not expecting to see her again, so I simply marveled at how strong an impression the aroma had left on me; I remembered it better than the curve of her hips.

And that led to a random revelation about art: No one has ever figured out how to make the primal sense of smell into a legitimate school. Forget perfumery—perfume is a mask, generally an outrage, an enhancement rather than a statement, the opposite of what art should be. The art of smell is a trick that other species—those less enamored of gallery openings and blue ribbons at art fairs—have mastered with relative ease. For example, over a couple weeks each spring, an apple tree—without a brain or an artistic essence—manages to wrest from the earth the requisite elements to juggle out a substance of indescribable beauty. In terms of evolution, it’s a fairly recent innovation too: No dinosaur ever saw an apple blossom, or for that matter, any flower.

For the interim, that’s where I left it. Back in the loft, I had my mise-en-place, and I had my inspiration for two, whimsical, life-sized portraits, and then a third one that I added as a nod to Alyssa. I was by no means a caricature artist and I knew my limitations. Instead, I relied on tones and value patterns, flattening the figures and simplifying the details. As for a personal style, I intended to hit the ground running: Conceptual art with a sense of humor and a message, and within a week I had completed all three paintings: ‘Cleaver’ depicted the black revolutionary Eldridge Cleaver handing a cleaver to Jerry Mathers; ‘Material Virgin’ was of pop-star Madonna in a classic Botticelli pose, only cradling a boom-box instead of the Christ Child. Finally, as a nod to Alyssa, I did a painting of Ty Cobb in a batter’s crouch with a corn cob instead of a bat, and called it ‘Psych-Out Fielder.’

Looking back, it was abysmal, gassy stuff, but I was willing to hone as I went. I’m embarrassed by it now, but I certainly wasn’t then—in any case, I wanted instant feedback, and I sent images of the work around to the few local art houses amenable to non-established names. Within twenty-four hours I heard back from Lauryn Posner, owner of Galerie Blu-Faith on Grand River, who wrote, “I’d have to view in person, but I think I like these. I’m not sure where the light is coming from, but I will say that your work seems to invite you inside to find out.”

We made arrangements for her to visit the loft the following week, and that afternoon I was so charged and—frankly—so competitive that I called Diamond Artist Supply and tracked down the clerk who had sold me the gouache. “You introduced me to a muralist called Alyssa, remember? She told me I could see her work at some restaurant, but I forgot to write down the name.”

He hesitated, but he was a quick study; another minute and I’d convinced him to give me the name of a sports bar in the northern suburb of Lake Britten, and I made the forty-minute drive. On a Friday night, the bar was packed; it was an old, established place that attracted local families as well as rowdy, upscale professionals and drunken good old boys who looked like they huffed gasoline from tractors.

I hadn’t even ordered a beer before Alyssa appeared in her gawky restaurant garb. “Gouache Guy,” she said, looking neither fazed nor the slightest bit happy to see me.

I apologized for the unannounced stalk and blamed the clerk at Diamond for giving up the goods.

“I know,” she said. “He called and told me. Thing is, I’m working. Were you thinking of fucking me on my break?”

“Oh, God,” I said. “I came to see your mural.”

“Cool, it’s in the game room,” she said and turned away. I read it as a take-no-prisoners brush-off until she turned back and said, in afterthought, looking at the wide screen TV where Tiger Woods was stuck in a sand trap: “All I have time for on breaks is one cigarette and I only smoke after sex—never during.”

On other nights, in other years, I’d return to that bar simply to watch her work, sliding from table to table, delivering pithy, gag-laden service, always with an air of dignity. She was very popular because her customers got what they wanted from her, which meant that she got what she needed from them, and this allowed her to earn a spookily adequate income. I phrase it this way because it trapped her; the job offered her sufficient cash to cover basics, which meant that she never had to muster the ambition to do anything else. She’d deny it, but in the restaurant she was in her element—appreciated and protected within an arsenal of disguises. She was waiting tables there five years before I met her and ten years later, she was still doing it.

That night I sat at the bar next to a giant man with a giant beard who had been weighing the exchange I’d just had with Alyssa, and when she’d slipped back into the rush, he considered me wary disgust. I supposed he was one of her fans and there was no value in a confrontation. I asked about the game room and he snorted, then jerked a thumb over a fat left shoulder.

I found it, but it took me a minute to find the mural; the room was filled rambunctious kids jamming flashing machines with tokens. Between humming and screeching from Talon and Maniac and Nick-Toons, the wall was covered in license plates from classic cars and photographs of Lake Britten when it was vacation village instead of a gentrified bedroom community. It did not look like a forum for a mural, and it wasn’t: I finally identified Ty Cobb’s face glaring through red-rimmed eyes, but the rest of him was entirely hidden by a pinball machine. It was the only game not occupied and I had to pull it away from the wall to see the entire painting.

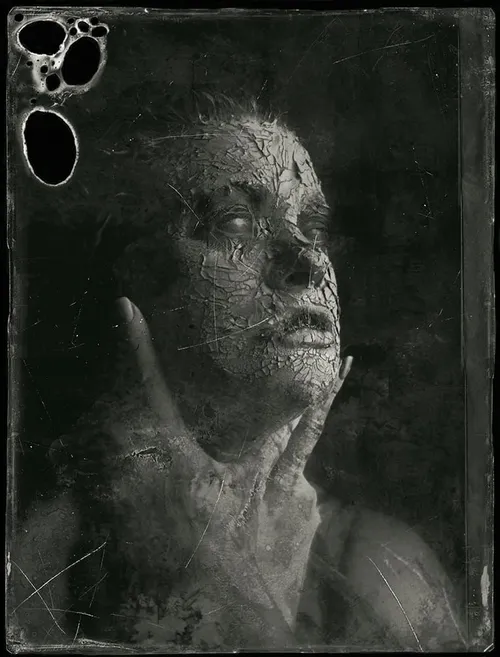

It is impossible to adequately describe its potency, so I’ll stick to a technical account, then ask you to trust my awe and imagine it. Where my Ty Cobb was built around colors and remained fixed in two dimensions, Alyssa’s Ty Cobb began bright, then mutated into some alternate and darker dimension. The features on the left side of the face were Cobb’s—I knew this because I’d referenced enough grainy images of him—but then they became reptilian and elongated. To the left, the crowd shimmered in anticipation, but and by the time she reached Cobb’s lower chin, his mouth had been dragged down began to fuse with the fans who, in turns, looked anxious then, terrified. I could not imagine a likeness that was more removed from the surface truth of photographs and more imbued in psychotic reality: This was the genuine Ty Cobb with all his brutality and nuance of impending disaster.

I was still looking at it when I realized that Alyssa was standing behind me with a tray of empty beer steins.

“Yeah?” she asked.

“I’m confused. Why would someone commission a mural then cover it up?”

“Oh, he didn’t exactly commission it; I volunteered to do it for free on my days off.”

“It’s phenomenal. Totally not what I expected. Why is there a pinball machine in front of it?”

“The owner thought it would scare the kids.”

“These kids? They’d love it. Hasn’t he seen the movies they watch? They have no idea who Ty Cobb is—to them, it’s pure creepshow.”

“Right?” she frowned; there was a wisp of defeat in the tone that was revealing—people do this when they are growing used to a self they’d convert if they could, but can’t.

“Cobb is one of the owner’s heroes,” she sighed. “I tried to do a straight-up portrait, but I got lost. Apparently, I let him down.”

‘Well, if it’s any consolation, you let me up. I’m blown away.”

She shrugged and shook her head, “I shouldn’t have read up on him first. I got so detoured inside him I never found my way back—I guess his soul kept seeping out from between my fingers.”

In my Cobb, nothing had seeped between my fingers but alla-prima paint and it showed. Mine offered nothing but objective outward appearance and the joke was a bad-pun bomb. Ty Cobb was not a name or a specific career highlight; he was a complicated and violent sociopath. I’d named my painting correctly and gotten the likeness wrong. Originally I was intended to show her my version and to tell her what the gallery owner had said about it, but now I thought better of it. Instead, I asked her what time she finished work.

“Around ten,” she answered. “Band practice night. Come by if you want. I’m the blue house, third one down off Ravine. It’s country, so there’s half a mile between houses.”

“Is your band as emotional as your murals?”

“Worse,” she said. “Especially after a few bong rips. That’s something I’m willing to do during.”

She returned to her tables and I found my car in the busy lot. I wasn’t eager to share her with a band that evening, but she’d given me directions to her house—even knowing that I was wont to show up unexpectedly—and I was curious, at least, to see it. I found the street by asking at a gas station and took an ungraded dirt road down a couple miles until I came to a single-story clapboard shanty, third one on the right. It may have been pale blue in a former life, but in this one it was peeling and forlorn, in need of a new roof and a lawn service. An old rowboat leaned halfhazardly against a garage door and chairs were arranged around an upended Home Depot buckets stacked with empty booze bottles. In the years that followed, I grew close to this house and the cindery embankment that fell away to an abandoned, rain-filled quarry out back, but at the time, it startled me by its loneliness and I decided to forego a plan to come by later to see if my hormones could outlast a band practice.

Had I not had a peculiar experience in the first mile of the interstate, I might have made it all the way back to the loft. As it happened, I came upon a Ford Explorer parked haywire in the median with the front driver’s quarter panel crushed. A hundred feet into a grassy field, a heavyset woman sat Indian-style, cradling in her lap the head of a wounded deer. She’d struck the animal moments before, and I stopped to see if I could help. As I approached, I saw that the doe was beyond saving—the tongue was red and lolled from the mouth—but she was conscious and in her final moments, locked inside a strangely glorious communion with the woman who had killed her. I was intruding; the woman was sobbing and the deer was gasping. I sounded more lame than pragmatic as I said, “There’s nothing you can do.”

“Do you happen to have a gun?” she asked without looking up.

“No.”

“I don’t either,” she answered, and I stood doing what I could—nothing—until my presence became utterly pointless and I backed all the way to my car, throat tightening and tears began to well.

It was the hopelessness of happenstance, and weeping over it left me feeling silly and hollow. I no longer wanted to skulk back downtown alone, so I stopped at a convenience store and bought a six-pack of Two Hearted Ale and found a pretty cemetery overlooking Lake Britten where I sat and watched the sun go down, the moon rise up and the stars cartwheel through the ink.

The private thoughts I knitted together during those hours, insignificant or monumental, have no real bearing on this narrative except perhaps in my realization that we are all equally biodegradable, painters and heavy women and road kill. And that Donne’s sentence—one of the greatest ever composed in English—‘Any man’s death diminishes me because I am involved in mankind’ might be upgraded to, ‘Any death diminishes me because I am involved in life.’

At around midnight, the good news from the art gallery had reignited in my imagination and supplanted my existentialist blues. Mildly buzzed and palpably restless, I cruised by Alyssa’s house again and this time the gravel driveway was thick with honky-tonk vehicles: A Ram 2500 Diesel fitted with a lift kit and tractor tires, a Softail Deuce, a rusting Carousel with cardboard over the drop-down rear window and an old blue Dodge Neon with the passenger door wired shut. The peeling blue shanty now glowed like a phosphorescent creature and the clapboards could not contain the thrum.

I left my car on the shoulder of the road and crossed the weedy lot, wending around the lawn chairs and the booze bottles; the rowboat against the garage, I noted, was called the S.S. Tin Can. The front door was open, and that was good because knocking would have been lost in the percussion.

The inside was scantily furnished and dominated by paintings; the biggest one hung over the ratty sofa and appeared to be painted on two doors bracketed in the middle and mounted horizontally. It was of a familiar scene, done from the perspective of someone sitting at the bar in her restaurant very near where I had sat and looking into the mirror between the liquor bottles and the wide-screen television. Like the classic Manet scene at Folies-Bergère, the viewer saw everything in reflection—the customers, the jammed tables, the servers scudding by with loaded trays. Alyssa’s painted world was vivid and skewed, and everything in it was undergoing the same metamorphosis as Ty Cobb, throbbing and dissolving and defying a still-life’s obligation to remain still.

So far, my works were colorful in execution but colorless in function; Alyssa’s had a tangible connection with inhuman experience. I recalled a film about an alien takeover where you needed special glasses to identify rogue earthlings—Alyssa seemed to have been born with pair. Her subjects could not stay surface; their deformities boiled through their pores and spilled across the canvas. Diane Arbus once found freaks hidden in the interstices of the ordinary, but to Alyssa, the freaks were lurking not among us, but inside us.

The other paintings were just as intense and I won’t belabor this with too many details; again, you’ll have to trust me. The light she found was unearthly; her characters were hybrids, steeped in corruption and trapped in the gravity of private handicaps. It was as if she painted in soot and blood. Had her interpretations seemed forced or heavy-handed, they would have failed as badly my dopey puns had failed, but they didn’t. These were life-drawings; metaphysical nudity without the slightest sexual connotation, and they were uniformly genius and unyieldingly menacing.

Years later, Alyssa told me that she considered my paintings to be menacing, though they were not intended to be. She saw in them soul-less precision, and nothing scared her more—or amused her more—than superficial humanity.

Alyssa’s house had an aroma of its own, like all houses do. During my first venture inside it, I only vaguely associated it with her. It was an old house, and the smell was likely a blend of generations; perhaps the paintings were emitting a scent of their own only peripherally related to Alyssa, like her vomit.

There was no one on the main floor but me so I followed the noise down to the basement and that’s where I first watched Alyssa’s band embroiled in their weekly rehearsal. ‘Big Hats, No Cattle’ also had no cohesion, and if they had talent, it was obscured by din and fury. I’m not a competent music critic, but I do know good from bad, and however awful ‘Big Hats, No Cattle’ was, it was made worse by being overdriven through bad second-hand equipment.

I’d get to know each member better over time: Bear was the big dude who’d been sitting next to me at the bar; he was wailing away on a mouth harp and seemed rationally competent, but come on—a harmonica is one step above a kazoo. Sty played electric bass; he was a plodding, lanky dude with tan hair hanging his face—the back of his hands were spotted with freckles. Bosco, the off-key fiddle player, had the carriage of a clumsy calf, an underslung jaw and lips like a fish.

Among the entourage, the drummer was the physical standout and I rightly guessed that the Harley belonged to him. His features were coarse, almost vulgar; at one time he’d broken his nose and it not been properly set. Yet the face was ineffably and undeniably beautiful, due in part to transparent metallic eyes that bored out without a route back in. There are men that other men immediately recognize as threatening, esoterically and physically, and although everyone is unique, there are genres into which people fit via artifice or accident. The drummer was one I recognized: A biker version of the Marlboro Man; all brutal charm and unquestionable masculinity. His name was Lee Halston and it turned out that he was (and would remain) Alyssa’s part-time lover. He was drumming for this shitty band only because she’d asked him to, and I’d be dealing with his hard-jawed good looks one way or the other over the next decade. In the moment I hadn’t yet worked out any sexual dynamic, but Lee had; he threw me a surly, underworld glare as I plopped on a chair beside an old terrier who, being totally deaf, was immune to the racket.

I’ll say this about Lee, though: He had terrific hands. His drumming was the power punch that gave the band a modicum of authority, and I later learned that he’d been in other bands that had opened for Seger and Springsteen.

That night, of course, it was Alyssa who commanded my attention; she was sitting on a stool in the foreground, spanking a steel string, saving my day and lofting me above the discord. Her voice was punchy and pissed, inundated with full-bodied notes, although the acoustics in the basement were so bad I couldn’t decipher a single lyric.

When that song was finished, she laughed and said, “Okay, Gouache Guy—paint us your review.”

The idea of seduction at the tail end of the clatter had not yet entirely abandoned me, so I saw no up-side to insulting her band. I said, “That’s a country song, right?”

“A country song? My man, that’s the country song; the synthesis of stupidity and idealized misbehavior.”

“What’s it called?” I asked.

“If You’re Leaving Walk Out Backwards So I’ll Think You’re Comin’ In.”

Whoa; that was as bad as Madonna with Boom-box. I didn’t go there: “I just showed up,” I said. “My ears need to adjust. I withhold an opinion—carry on.”

They did, playing several more numbers while I sucked down the last two Bell’s. An ancient little mutt climbed into my lap looking for a belly rub—reminding me, alas, of a dying deer. The group got no tighter, and they were finished when Lee decided they were finished. Unable to take any more, he stood up, tossed his sticks at an old furnace and moved to a lacquer table loaded with overfilled ashtrays and a two-foot beaker bong.

The others dribbled over to a refrigerator and pulled out beers. We introduced ourselves with nods and mumbles; Lee packed the bong with weed from a pocket stash and Glenn cried in a tone of appreciation, “Yow! White Widow.”

Alyssa remained on her stool: “Remember me? This is the part of the show where the audience demands an encore and I do a solo number.”

‘By all means,” I said. “Please. Something you wrote, I hope.”

“I only sing songs I write,” she said.

The calfy fiddle player chimed in: “Do the one about Lee.”

“If he doesn’t mind,” she said, tossing a glance toward the drummer. She sounded deferential, and for reasons which are probably obvious, I didn’t care for it.

But Lee was busy firing up the bong and didn’t even look up, so she dropped the pitch on some of the guitar strings, raised it on others, changing the tuning while the bong was passed around.

I’ll state for the jury that weed was never my particular interest, but I’d certainly smoked my share in high school. I didn’t want to look like a douche, so I took my lungful in turn, which was a mistake because this was my first experience with bong shotguns and I fell into a ridiculous fit of coughing. My reaction made Glenn say ‘Yow’ again as he added in my defense, “I have out-of-body experiences every time I get do this shit.”

Alyssa looked at me with amusement while saying, “You gonna go whitey in the bathroom, dude, or can I play my song?”

I cleared my throat and answered, “Lee’s song?”

“It’s my song, darling—promise—dedicated to all such brooders; men with built-in hideaway rooms where they sit and gloat over life like a miser with gold.”

By Lee’s expression I believe he was perfectly satisfied with this description. He pulled a last cigarette, crumpled it up the empty pack and began to bounce it in his hand like a ball. Casually, before she began to play, Alyssa tossed him another pack—and that’s when their relationship first dawned on me.

The dope was stronger than any I’d ever smoked before and it hit me quickly and made my brain shudder—I felt foreign fields of energy, as if I had fallen into one of the Alyssa’s paintings. Combined with the IPAs I’d downed, a blanket fog spread over me, making the scene ethereal and haunting and almost dreamlike in my memory. The piece Alyssa played was called ‘Lost But Found’ and the altered tuning remade the guitar space with tonal shifts far removed from three-chord country progressions.

Her voice was as clear as an atmosphere and the lyrics went, in part, “…you weren’t there when I was crib-bound, you came too late for that; you arrived like lead wind shivering the thin pine frames.” She sang about a dusty and bristly torso and clutching love, of final chapters that leave one blank; the chorus ran: “Lost but found, dry or flood, with you it’s nothing but business or blood.”

I loved the words although I had no idea what they meant. Alyssa said, “Men have to go over the line when they sing a song. All a woman has to do is get near it. I’m a preacher passing on Girl Gospel, son. Very near that line”

I asked her where she’d learned to play guitar, and, on the way back from the refrigerator, where she got me a beer and a bottle of vodka from the freezer for herself, she laughed, “Can you believe it? From an old Pete Seeger instruction record my grandmother had laying around”

That was the last direct exchange we had. One by one, the others began to talk about how and when they’d wound up with their instruments. Pressed to the point of irritation, Lee shrugged and mumbled, “School band. The teacher decided who got what. The fat dudes got the big horns, and athletic-looking guys got the drums.”

“Do you play?” Sty asked and I answered, “Nope. I wasn’t fat or athletic, so they stuck me in Shop.”

Alyssa hit the bong twice in succession and did not cough at all. From that point, the group dissolved into one-track dope rap, talking about dank shake, bud men, pooching bowls that were pure milk and getting hit by the bakedness train. Bear launched a story about the time his RooR dab rig did a backflip off his desk and landed mouth-end on a hardwood floor. That, apparently, was a sad day and every head shook in dismay.

I added a few random observations, but again, because of how fucking high I was—nearly tripping—my voice sounded like it had been tape-recorded and was now playing back. I became increasingly uncomfortable; like my experience with the woman and the deer, I had inserted myself into a private world where I did not belong. I was a meteor crashing into one-big-family house-party bonhomie and my ego suffered as much as my head, so I made an excuse during a lull and said my goodbyes to the humans, scratched the dog’s belly a final time and stumbled upstairs.

Alyssa followed and met me at the door. “I know those guys are a handful, but I’ve known them since forever. Comfort and reassurance, you know. It makes you overlook a lot.”

“It’s fine,” I said and I meant it—they weren’t out of place, I was.

“You look like you maybe shouldn’t drive, though.”

“I think I’ll be alright.”

“I think you should maybe stay here anyway. My room is down the hall, left, opposite the can. You can have my bed.”

“If I did that, where would you sleep?”

“In my bed, ya doorknob.”

“Aren’t you sleeping with the drummer?”

“Not tonight,” she answered.

I found Alyssa’s bed without turning on the light and lay there awake, waiting for her. The room was saturated in her scent; no trace of anyone else lingered here. This was a potent condensation of the smells I remembered from Diamond Artist Supply.

Stoned minds find wormholes and they are rarely good for the psyche: Again I thought of apple blossoms—those pretty morsels that showed up after the dinosaurs died, but—significantly—before humans arrived. This lovely smell is not intended for you and me—we can offer a tree nothing of value in return, and a tree has neither the need nor the framework to appreciate our appreciation. Does the insect for whom this fragrance is created relish in its singular splendor? I’m not a bee, so I don’t know for sure, but I assume that bee is reacting to imperatives unrelated to aesthetics. I say this because there are other flowers—those pollinated by flesh-eaters—that mimic the smell of decaying meat. If insects are driven by art, does it mean that humans have not evolved sufficiently to find beauty in the scent of a corpse?

With this grotesque image in mind, and despite myself, I nodded into a dope and ale coma; I was awakened by a voice in my ear whisper-singing, “Don't come home a drinkin' with lovin' on your mind.”

I stirred. “Are you drunk?” I asked.

“Totally,” she murmured. “Lam-fucking-basted.”

“That’s a shame,” I said.

“Not when you find out the things I do drunk that I don’t do sober,” she said.

I was in a narcotic borderland, and the hours that followed, though filled with sensuous evocation and conspicuously-plastered eloquence, are now mostly vanished. If I can only remember spasms and spurts, it’s not to say that the experience was not memorable—although I didn’t have the heart to point out that Alyssa’s opening line, sung gently in my ear, had been a verse from somebody else’s song.

2.

I did not pursue Alyssa romantically; her friends were loyal and her biker thug boyfriend did not seem the type to suffer horny persistence fondly. I was satisfied to keep it as a one-nighter. As teenagers we’d called it ‘scoring’, but in ways it’s how we end up losing the game.

Over the next week, in advance of the visit from the owner of Blu-Faith, I re-envisioned my scope of work. I stacked the silly trio of pun paintings in a corner and set out to do better ones. I couldn’t match Alyssa’s knack for turning organisms inside out and exposing their personalities, nor did I want to: I couldn’t imagine her bar scene painting hanging anywhere but in her living room and I wanted my stuff to appeal to sleek Deco minimalists with deep pockets and empty walls. I began to work with unique compositions, geometric shapes and colorful graphics; I borrowed from academic painters and the principals of Bauhaus design. This time, I forwent recognizable celebrities for recognizable archetypes, juxtaposing men in suits with naked men, nubile young women against stark backgrounds, including one who was cinematically cropped, smiling and waving from a red convertible.

I painted as an engineer more than as an artist; a eureka moment in which I found my niche.

Lauryn Posner thought so too. When she came to the loft for our appointment she was tangentially surprised and confidently impressed by the improvements she saw. I conceded that the bad joke stuff had been a misstep and she agreed: “I assumed you’d outgrow it and lo and behold, it only took a couple weeks.”

“I’m still working out the technics,” I said.

“My dad would appreciate that approach,” she answered.

Lauryn had a number of earnest suggestions, which might easily have been interpreted as having a plan for me, so I brought out the wine I had chilled, and as we sat on the furniture I had imported for the occasion, she told me about the plan for her.

Her father was Morrie Posner, a well-known dealer who’d made a fortune in cruise-line auctions—an ingenious innovation in marketing high-end art. Like me, Morrie had started out as mechanical engineer, and had approached the art world practically, awed by the price of the nuts and bolts as much as by their beauty. His manufacturing and distributing experience had allowed him to apply ‘best practice’ strategies to shipping operations and to streamline the journey from studio to collector, with the bonus of becoming a fixture on every elite international cruise ship on the planet. In fact, Lauryn had just returned from such an excursion in the Aegean Sea, which explained why Blu-Faith had been closed the several times I’d driven by it. ‘Gallery Hours’ was a term I’d get used to—it meant you opened when you felt like opening.

I had no reason to contrast Lauryn Posner with Alyssa, but I did it anyway. Lauryn was angular-tall, with glossy black hair and striking alabaster skin interrupted only by a spackle of freckles that ran in a constellation across her cheeks. They turned out to be a Semitic tan since they faded not long after she got out of the sun. She was a year older than me, but still retained a little adolescent optimism: Her father had bankrolled Blu-Faith as a sort of trial run experience in managing a business in the hope that she’d one day join the family firm. But Lauryn was not ready to forgo a destiny she alone controlled, and in the three years since opening, she’d turned her gallery into a defining center for the city’s underground art scene; a raw, eclectic mecca for poetry readings and avant-garde theater performances. She ran art appreciation classes for underprivileged youth in the area and above all, she loved to showcase promising unknowns: Enter me.

Behind Lauryn’s altruism was a mercenary lantern held out in a search for the next Gerhard Richter, one of her father’s early discoveries. We hadn’t finished the wine before she offered me a gallery show in November if I thought I was up to producing twenty canvases, five feet or so in height, by the end of October.

“Am I? Are you questioning my ability to execute or to be inspired?” I asked her seriously.

“Neither,” she said. “I’m an observer; I see the drive is there—it’s all over you, like spilled paint. It’s style cohesion that would be a concern. The stuff you sent me originally had an insecurity about it. That seems to have settled out. To me, the girl in the sports car marks the change. Do twenty pieces as firm and durable and we’ll show the best ten. You’d want more of people in groups; I’ll send you a video on pouncing that will help you with composition—it shows you how to pin paper silhouettes to the canvas and pounce dry pigment through pinholes to make the outlines. Oh, and I’d also like to introduce you to Max Simon.”

The only Max Simon I knew of had made his mark by developing suburban shopping centers; he’d been on the Forbes 400 Richest Americans list for decades. “The mall guy?” I asked.

“Yeah, the mall guy,” she answered. “Also, you may know, a connoisseur of New Realists.”

I didn’t know that—I was still a newbie the art world and I admitted it frankly.

“That’s fine, I get it. Max, you should know. He’s nearly ninety, but he still likes to be on the bubble with emerging talent. He’ll be an asset—there hasn’t been a collector as ravenous as him since Herman Goering.”

She winked at an irony I didn’t yet get; I found out later that Nazis had plundered the Simon estate in Antwerp after sending Max and his parents to Buchenwald; Max was the only member of his family to have survived.

That night, Lauryn took me to Dépanneur, a trendy hang-out restaurant downtown. It happened that we had a lot in common; she was the only other person I knew who’d read The Eater of Darkness, a surrealist Robert M. Coates novel from 1926. Neither would allow the other to pay, so we wound up splitting the tab and at the evening’s end, I shook her white hand and both of us detected within the gesture both warmth and portent.

Lauryn had maintained that what she liked about my work was that it was cool without being cold, so that’s the quality on which I tried to capitalize. I took textural cues from colorists like Cybis and Gauguin and sheathed my images in candy-coated brilliance. Inspiration was everywhere; if Lauryn liked the girl in the red convertible, she’d love the Japanese girl with a rose bud. If she’d been moved by the ultramarines of ‘Swimmers at Midnight’ she’d feel the wind blow through ‘Dunes in December.’

I switched from gouache to oil after watching another one of Lauryn’s instructional tapes, this one with Juan Gomez demonstrating the technique applying five undercoats to the canvas—three of gesso and two of lead white. It dramatically altered the way the light played in the finished painting. Lauryn had explained that to market art like mine, it was paramount to force an instantaneous response of the viewer and light was the quickest path. I was aware of how effortlessly Alyssa was able to do it, but I wasn’t interested in producing the sort of gut-wrenching emotion that comes with organic dissolution—I wanted wake-up glare from primary pigment. I wanted work that would hang prominently in penthouses on Central Park South, not be hidden behind a pinball machine in Lake Britten.

I was a month into constructing these paintings when Alyssa called. Lex talionis; she’d wrangled my number from the card I’d left with the clerk at Diamond Artist Supply. I was surprised, a bit intrigued and a lot confused since I had wrongly assumed that casual sexual encounters were routine in her universe and that I was now a faded memory. She’d readily taken me into her bedroom with her boyfriend downstairs; we’d shared surface and a little depth, but we were vessels who had collided accidentally, then intimately, but had continued on our way. Now she was crying into the mouthpiece, and for a shivery moment I assumed she was going to tell me she was pregnant.

But the call was about Bill, her miniature, flea-bitten mutt: She’d decided to have him euthanized, then decided against it, then in favor of it, and shortly after the pendulum swung one way, back it came the other way. I recognized that she was shit-faced drunk at four in the afternoon and needed to emote as much as to solicit advice. Why my advice? She guessed that I’d see a practical side, and once the wave pulled back from the shore a bit and her tears subsided, I did.

I told her that if it was me, I’d make a basic list of things the poor little guy used to enjoy doing, like chasing balls or fetching sticks or rolling in shit, and if he no longer dug, say, three or four of five things, it was probably time to consider saying goodbye. ‘Rolling in shit’ cracked her up and she giggled for a minute, and coming in the midst her turmoil, I found the sound to be precious. She thanked me, apologized for bothering me, and twenty minutes later she called again later, drunker than before and more hysterical and said that she done the checklist and Bill failed five of five, including the one about rolling in shit. She’d made an appointment at the vet for the following day and asked me if I would come along.

“Me?” I said. “Why not somebody who knows you a little better? Your history with the dog? What about Lee?”

“Lee’s on tour with some metal-head band. Plus, this is heavy shit. Lee does stomp. He doesn’t do emotional.”

“What makes you think I do?”

“Because that night you stayed with me, you told me about a woman with a dying deer and you cried over it.”

Oh, God. Had I? There was a lot about that evening I didn’t remember.

“Come with me tomorrow,” she pleaded. “Afterward, if you want, I’ll remind you about the best parts.”

My own pendulum wobbled—had I painted myself as someone willing to trade an act of kindness for a blowjob, a corruption of an eye-for-an-eye, a heart for a tongue? That’s some mutating mural shit right there. But it made me consider the extent to which we exist simply as reflections of who others think we are. What if we have no self outside ourselves and we’re only a consolidation of impressions? Alyssa herself was a puzzle I’d work on over time, but that day, I was a long way from solving it. At eight the following morning, two hours in advance of the vet appointment, I pulled up to the third house on Ravine Street.

She embraced me, and there was nothing to misconstrue in the warmth or in the booze already on her breath. We didn’t mention the dog. Instead, I looked over the painting she was working on. I recognized the subject at once, and I don’t think many from our generation would have, and from that point, Jaco Pastorius—the tragic jazz bassist—occupied the same plateau in our friendship as Robert M. Coates did with Lauryn and me.

Her portrait captured Pastorius in the midst of his final bathos. His arms were serpentine; his fingers fluttered after something beyond reach, settling instead for a portfolio of impossibly perfect notes. His heavy-lidded eyes were manic and exhausted—he looked ready to spring and ready to succumb. Above his sweet, sad face she’d painted a red corona and I asked her if it was a way of sainting him. She showed me a copy of magazine story from 1987 that lead with the sentence, “On September 12, in the darkened alley behind a strip shopping mall in Wilton Manors and less than an eighth of a mile from a police station, jazz legend Jaco Pastorius was found in a halo of his own blood.”

Pastorius—whose musical genius has been likened to Mozart’s—had been beaten unconscious by a bouncer at a nearby nightclub and died a week later at the age of 35. Since he was drunk and belligerent at the time, it was impossible to assign blame to anyone but him, so naturally, those who loved and respected him assigned blame to everyone except him.

As a backdrop, Alyssa had created a tropical beach spiked by sinuous palm trees, and inexplicably (to me) a parked car and a baby in a crib. When I asked about the significance, she pointed out a quote in the article in which Pastorius’ kid brother had said, “Jaco heard music in everything. A baby crying. A car passing by. The wind in the palm trees. All of a sudden, he’d say to me, ‘Shhh!’ and he’d listen. I didn’t hear a thing.”

Neither did Alyssa’s deaf, doomed terrier who climbed weakly, if warily onto my lap as Alyssa put on a CD of the Newport Jazz Festival. We sat together and listened to Jaco Pastorius play an hour-long solo while I drank coffee and Alyssa drank vodka and cranberry juice and sniffled. We took turns scratching and soothing poor trembling Bill, who I think was beginning to catch on. I remarked, “You realize that if you’d have put belly rubs on his ‘like’ list, we might not be sitting here?”

She laughed, but it didn’t win Bill a stay. Amid the devotional applause of the Newport crowd, zero hour arrived and we loaded the dog gently into the rear seat of the Neon. I drove while she cradled Bill amid blankets and chew toys. One of her rear windows was stuck halfway down, and five minutes before we reached the vet, in some haunted sense of canine precognition, he wriggled from her arms and leaped through the window and skittered into oncoming traffic.

She tore after him, oblivious to vehicles and screeching brakes, chasing him from shoulder to shoulder, dodging cars until I could arrange myself in a way to stop traffic, which I held back until Bill’s energy finally failed him and she cornered him in the median.

If you want to be a painter of original works, you develop a snap-shot mind for evocative images. For me, that morning contained two: The first was Alyssa, sitting in the strip of M-24 clutching a terrified dog, laughing and sobbing at the insanity of having just saved him from certain death half an hour before she paid to have him killed. The second came exactly half an hour later, on the floor of the vet, in a corner beneath a poster of a healthy dog, when she held Bill as he was killed. The poses were nearly identical.

Bill’s defiant highway burst had nearly finished him, and in the end, he had nothing to give life but a twitch and an exhale as his heart and brain shut down. He left the world quickly, with his heavy-lidded eyes half-open like Jaco Pastorius in his portrait. Afterward, we bundled the little corpse in his favorite blanket and took him back to the car. Alyssa told me that she had already dug a grave in the rear of her house, beneath a willow tree overlooking the small lake that had formed in the abandoned quarry. “That’s where I had my baptism,” she said. “And where Bill loved to swim.”

It sounded sweet, so I was surprised that on the ride back she wanted to stop at Britten Brewhaus and drink.

“Why is that strange? The bartender has known me since the day I was born. I thought he’d want to raise a glass to my newly-deceased roommate.”

“Don’t take this wrong,” I answered delicately, “Only, it’s a hot day and we should probably think about getting Bill in the ground sooner rather than later.”

“How long before he starts to smell?” she asked, blinking in mock incredulity. “In your estimation?”

“I really don’t know, Alyssa. Not immediately. Probably not until tomorrow.”

“Oh, because I wasn’t thinking about spending the night at the bar.”

“I know,” I replied. “I’m sorry.”

“Actually, I was thinking of spending the night in my own house. In my own bed. With you and the crazy moon and the ghost of Bill. So, now that the hard part is over, what is it exactly that you want, Gouache Guy?”

“Honestly, Alyssa, the bar is cool. We have time for a drink—let’s go toast Bill and the moon and the day you were born. But since you’re asking, I’d like it if someday you showed me what you can do sober. For contrast.”

“Honey, about all I do when I’m sober is look for something to drink.”

So, that wound up being a keystone in the structure: Alyssa was a drunk, with no euphemism better suited to describe her. She didn’t get mean or maudlin; I never saw her violent or irrational, and in fact, after half a fifth she became more lucid, especially in her art. “I must be a conduit,” she told me once, and was as surprised as anyone that when she was otherwise blotto, her voice became gentler and more precise and her painting became richer and darker: “It must be something from outside going through me, bypassing the sponge that’s supposed to be my brain. Apparently, I’m a conductor.”

I didn’t know how she did it, but I also didn’t know why: I drank normally and rarely to excess and although I did blow occasionally, I never did enough to do damage—I liked myself too much for that.

Over the next few months, I saw Alyssa several more times, always on a whim and naturally, never when there was a Harley parked in the driveway. Those occasions were sodden with pheromones and Grey Goose, or whatever offering I brought along to exchange for her scent and her nonsense and her soft, charming company. I was endlessly bemused and fascinated by the way she skirted through contradictions; she did fantastically deep artwork, yet thought that the old sitcom Green Acres was the funniest program ever made. Her lyrics were as insightful as they come, but when I’d sometimes take her day-drinking at the Britten Brewhaus she’d jam money in the jukebox and play the worst that country had to offer, insisting that she loved it.

In late September we ended up at Lake Britten Urgent Care when she toppled off her stool and split open her skull on the lacquer table in the basement; she’d been playing guitar with such dash and control that I hadn’t realized how drunk she was. At the clinic they said her blood alcohol level was nearly .04%, potentially lethal for someone of her size. Consumption that obstinate left us at an emotional impasse because—art conduit or not—this was self-destruction at escape velocity.

After that I cooled it, and the next time I saw her was at my Blu-Faith opening. I’d been obligated to send her an invitation, of course, which I knew she wouldn’t see as gloating because it wasn’t: It was showcasing my style in an open space, where it worked. Alyssa could rightly lay claim to having offering me my first piece of painterly advice, and I wanted her to see a world where intelligent art made money and where pinball machines were not wedged up against the wares. I hoped she would not do a swan-dive into the champagne table.

She came with Lee Halston who lurked and sulked like Brando on a waterfront dock and smoked beneath signs forbidding smoking and blew clouds into the face of a poor assistant who pointed this out. Alyssa was wearing his patch-littered leather jacket over a peony-and-pansy-kimono with a massive Stetson that covered her head wound, still healing. She was boiled and beaming by the time she arrived, and after I introduced her around, I took Lauryn aside and asked her if she’d noticed Alyssa’s unique, encompassing scent.

“I didn’t think to check, but then again, I wasn’t aware that sniffing your little girlfriends was part of the arrangement,” said Lauryn—herself in a retro, camera-friendly Betty Blue dress and statement heels—and I was surprised to detect the note of pique.

I probably shouldn’t have been: In the weeks before the show, within my parallel universe, besides perfunctory, furious painting, I had begun to socializing with Lauryn and her circle of friends. In August, she had taken me the home of Max Simon—an arresting pair of glass and steel structures nestled into fifty sprawling acres in Lancaster Hills.

Prior to the introduction, I had read up on him; he’d shared much of his remarkable story in an archived New Yorker interview from 1975. He described a single experience in Buchenwald that had set him on his life’s course: “I was hit over the head with a guard’s rifle. When I came around, everything had become golden; people shimmered, buildings glowed, the sky was on fire. I thought I was in Heaven instead of in a death camp.”

He also claimed that hallucination had not entirely left him: “I still see colors that others miss.”

After the war, in fact, he’d studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts and immigrated to New York primarily because of its color: “In those days, the whites of Paris had turned grey. London was green, Antwerp black. I considered Tel Aviv to be blue, but blue has no dimension; it is outside dimension. On the other hand, New York was red, and red is the color of life—the color of blood.”

Simon received Lauryn and myself in a central courtyard paved in honed stone with open rectangles greened with ground cover or planted with foxgloves and Icelandic poppies. He was wiry, agile, flawlessly bald and entirely lucid; he shared the gigantic house with a restaurant manager whom Lauryn had told me was his lover. We sat at a wire-framed table that he had designed and were served hibiscus tea by a handsome, black-clad young man with exquisite cheekbones, and for two fascinating hours, Simon regaled us with his theories of art and his quest for people who understood space the way he did. His shopping centers had won countless awards; many were garden cities—window-walled structures perched on concrete pilotis with parks and even tree groves interspersed.

“Artists are perpetual foreigners,” he said. “Not as implied by passports, but by vision. The great ones are those who can emerge from seclusion and meet the strangers in their own land.”

Later, while Lauryn went to make phone calls, Simon took me to the south wing of the house to show me the work of some of his favorite strangers, and naturally, they weren’t strangers to anyone who has read a Wiki entry on modern art: They were originals by Magritte, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Roberto Matta and Man Ray. There were Dadaist cartoons by Kurt Schwitters and an accumulation of animal traps by Jacques Villeglé. I ball-parked the collection’s worth at seventy million and guessed that Simon’s security system must also be a work of art.

In the room’s center was a life-sized female figure sculpted by Niki de Saint Phalle which combined humor and eroticism with social criticism. Of it, Simon said, “This is the point of convergence because more than the others, it defies authority. Defiance is the primary obligation of art, so this becomes your life command: In Hebrew, it’s tikkun olam—‘repair the world’. To excel at your discipline, it must define you as entirely as the war did me.”

I nodded, fully (and gratefully) in absorption mode. He added, “Disobedience is not how I was raised, mind you. We questioned nothing, and thus, passed from the arms of our nurses into the arms of our murderers. This piece is better than anything they have at the Modern. It represents de Saint Phalle’s liberation. I await yours, in whatever abstraction, and when I recognize it, I will hang it proudly in this room.”

Mall Guy floored Gouache Guy, and then there was more: “Until that happens, I have purchased ‘Girl with a Convertible’ for a speculative sum, more than the asking price. Every engine needs a primer. I will hang it in a different place, in a room full of fabrics and straw baskets and folk art, groupings unified solely by curation. The house is modern, but I have retained from childhood a love of Victorian clutter.”

And still more: On the way back to the courtyard, he took my arm as an uncle might and said, “Another thing I remember from childhood is that marriages were arranged by shadchanim. Love between the parties was a bonus, but not necessarily a requirement. Had the war not upended my world, I should have entered into such an arrangement, and done so happily since I loved and trusted my parents. As it is, I wound up with Michael, so we find a glow in the blackness.”

Ahead, Lauryn sat at the wire table texting with the same fury with which Alyssa painted. Before we arrived, Simon stopped me at a fully-grown Coulter pine emerging from a Deco planter and said, “I’ve known Lauryn Posner since the day she was born; her father and I sit on the board at B’nai B’rith. The two of you are a lot alike—prone to tangents and, I think, in need of anchors. If you haven’t already considered it, let me act as shadchan: Lauryn is a girl you should consider courting.”

3.

I hadn’t even considered considering a ‘courtship’, based in part on an unwritten rule summarized by Urban Dictionary as ‘don’t shit where you eat.’ For some lucky soul, Lauryn Posner was eminently spouse-worthy; she was beautiful and classy and heir to a fortune. Had such an arranged marriage actually been my obligation, I might have assumed that my anchorless ship had just come in. But my motives were different, and from the moment Lauryn first responded to my unsolicited email, I had viewed her with detached professionalism, and I was sure she felt the same about me.

More to the point, though, was Alyssa a tangent? The word implied a diversion from a pre-ordained course and I had none that I was aware of. Switching direction from an antiseptic corporate career to a precarious tightrope was more a rage against the machine than kismet, although along both paths I’d approached sexuality with an autopilot expectation that if it was consensual, there was no harm done.

Following the opening, we gathered at Dépanneur for an afterglow and I was the toast of the room because of how well the show had done. By then, Alyssa and Lee were long gone, as was my family. The latter had put in an appearance at Blu-Faith, for which I was grateful, especially for the look on my dad’s face when he learned that Max Simon—who owned 11% of the company for which he worked—had purchased one of my paintings for twenty thousand dollars. Even my brother had to begrudge me respect; he’d once alluded to my quarter-life crisis as effete and elite, but after that night, he never again dared to call my masculinity into question. I’d sold seven of the ten paintings—‘Girl with a Rose Bud’ to my mother, whose check (of course) I’d never cash. The others went to speculators, mostly on Simon’s advice.

Something in the triumph was missing though, and I was still awake at five the following morning, like a kid on the day after Christmas trying to figure out why getting everything you’d hoped for left you emptier than before.

And then, my phone rang. It was Alyssa in the sort of condition I would have expected her to be in at that time of day. Initially she wanted to thank me for inviting her, but then she wanted burble on about unrelated topics. I guessed that cocaine was in the formula, and had I not been awake already, I would probably have hung up. As it was, I was glad for the company, and shortly something potent took hold of me and I did something I hadn’t expected to do: I sent her a photograph of a painting I hadn’t shown at the exhibit: One of her and Bill in the dog’s final moment.

Silence was not her style, so when it followed, I assumed that sending it was a mistake. Finally, she said. “Why didn’t you hang this one with the others?

“Because the others are fluff. You holding your pet while he died isn’t. It’s private; I really wasn’t part of it. Painting it felt like an intrusion.”

Her voice began to break. “Oh, you were part of it. Remember what you whispered to me that first night? ‘Any death diminishes me because I am involved in life.’ Every portrait intrudes, sweet boy. That’s the whole point.”

In a quick exhale, I understood why I was restless: Despite having made a year’s salary in a single evening, I hadn’t moved anyone. I’d sold assets, not connections. This is what the other route felt like.

“I want to come over,” I said suddenly.

“Lee’s here.”

“Well, he was there the first time.”

“I know, but this time he’s here here. Eight-ball of flake here. Say-hello-into-the-phone kind of here. Say ‘hello’ into the phone, Lee.”

I heard a grunt. Alyssa said, “I’ll translate: ‘Thanks for a wonderful evening. Champagne is better for the soul than PBR and I know the girl in the red Corvette—she one of my groupies. P.S. Your pictures are nice.”

“Screw Lee. What did you think?”

“You’re in the club, Artist Formerly Known As Gouache Guy. Nice, obviously. But the one I saw at my private screening? That one is incredible.”

Alyssa didn’t ask for the painting of her and I didn’t volunteer it; I knew she’d display it, and not only would it have been out of place in her cramped house—it was big enough to need bigger—it would have be an endless reminder of that sad, frozen instant. Looking back, I wish I’d done differently: The painting was hers and what to do with it was her call to make, not mine. And even though I had ‘bigger’, I didn’t hang it either. I stashed in a corner of my studio and continued to paint investments.

On the Thursday following the opening, Max Simon asked me to meet him for lunch at The Grille in the exclusive, members-only DAC. Amid tablecloths and hardwood floors, he continued to dispense advice and I remained an eager student.

“By degree, you’re an engineer, he said, “so I’ll pose the dilemma as I would to an aircraft designer. You send ten fighter jets out on a mission where they encounter heavy fire. Seven return and three do not. You have no other information to work with; how do you design a safer plane?”

It was easy—that’s exactly how my mind works. “I find a schematic of the original design and highlight all the flak holes in the planes that came back. Then I reinforce every portion of the fuselage that doesn’t have a bullet hole in it, because that must be where the other three were hit.”

“Excellent,” he said, eyes twinkling. “You pass. The three paintings that didn’t sell are the fighters who did not return. Next time, you’ll know which weak spots to reinforce.”

Veal chops arrived and he said, “That reminds me: You remember Michael, whom you met in my home? He is managing the new Fiat-sponsored hotel on Gratiot, and they are working in an automotive motif. The hotel owners are currently evaluating artists to do a series of lobby murals—people and cars, cars and people. It’s a lucrative commission and I’ve tossed your name into the ring. You understand the automotive part well enough and you are improving quickly on the human element.”

I thanked him, although I figured it was a long shot even with his blessing—there were superb, established artists in the city who did hotel lobbies for a living.

The Grille was clubby and masculine, but dangling the Fiat carrot in front of me is not why he’d invited me alone, without Lauryn. I’d figured that out in advance and was waiting for it. Over coffee, it came: “Lauryn remains a bit damaged, although it’s a face she probably hasn’t shown you. Last year, she broke it off with her fiancé. David Silver is a lawyer on the brink of many successes, and he’ll make a fine husband for the right bride. But Lauryn was not the right bride. David doesn’t want a Lauryn, he wants a Hausfrau. He wants a children mommy, a domestic to clean the dishes and an accessory at the Jewish Community Center.”

“What makes you think I don’t want the same things?” I asked. “Except for the JCC part—I’m Episcopalian if I’m anything.”

“When I was a child, your faith would have been the unsurmountable mountain. These days, not so much. Lauryn’s parents never cared for David either. David thrives on status quo, and you reject it, or else you would not have imploded your safe career for art. This is a better match for Lauryn, who wishes to become the status quo. Together, with the two of you, perhaps this is possible. Anyway, I repeat myself like an old man; it’s just a consideration. Unless you are already spoken for. Are you?”

“Nope,” I answered, because I wasn’t.

Still, in the season that followed, I made a show otherwise. To my surprise—but not Lauryn’s—I was awarded the Fiat commission at the new hotel. It occupied me for many months, during which I made my own hours, and at times, a random link—often a smell in the air—reminded me of Alyssa and I’d visit her. There is an quirk in nostalgia, perhaps a flaw: We find ourselves missing scenes or events or smells that were, when they happened, neutral, and memorable only in context of other things that were happening at the same time. In that way, memory is unexplainably scattershot. What I could explain, if not rationalize, is that Alyssa’s scent was for me a distillation of desire and something I came to crave the way she did vodka.

On these occasions, she was so physically accommodating that to me it seemed weird. To her, it was even weirder that I saw sex as a transaction. I couldn’t shake the mindset and over the course of these encounters I redid her roof, hung new gutters and installed a state-of-the-art furnace in the basement. Had I done none of this, she still would have slept with me. “It’s called compatibility, silly” she’d say. “It’s the same with me and Lee. We’ve been fucking since we were thirteen. Compatibility doesn’t happen often, and when it does, you accept the full package—you don’t second guess it.”

But second guessing was part of my full package, and I continued to trade her frame and friendship for grunt work. I rented a dumpster to take away the fifty-year-old shingles I’d pried from her roof, and on the morning it was hauled away I noticed that Alyssa had thrown a painting into it. It was a landscape and I recognized the prospect: Her backyard with its focal point as the willow tree under which we’d buried Bill. In the background, the quarry pond lay still and silent.

I thought it was striking, and not only that, it was the only work of hers I’d ever seen that did not feature a human subject. But beneath the roofing dust, a closer look revealed an almost fractal array of human subjects. They were everywhere; faces writhing in the puffy clouds, sneers muffled in the tree bark, grimaces gurgling beneath the pond waters.

“Why did you throw this out?” I asked her later, genuinely baffled.

“It was an experiment. I wanted to try something serene, like you.”

“You don’t do serene,” I said. “That’s not your wheelhouse.”

“Right? It’s a disservice to the subject. I hate it—that’s why I threw it away.”

“Do you mind if take it?”

“I don’t know why you would,” she shrugged, “but knock yourself out.”

To this day, it is the only one of Alyssa’s paintings I own. I showed it to Max Simon once and he studied it for a while, then pronounced, “Grotesque. The artist has the vision of a death camp survivor. This is for nightmares, not display.”

I never told Alyssa what he said, although she would have agreed.

4.

Thinking back, the events of the next two years had an air of inevitability about them, like during the credits of a film when you suddenly grasp that the script could not have resolved itself satisfactorily in any other way. My Fiat murals were well-received and critics referred to them as ‘boldly colorful, high-intensity gems’ and called my style ‘confident and crisply articulated, with all but the most essential details pared away.’

After that, Lauryn’s father commissioned me to do a series of gallery paintings for a Norwegian cruise ship catering to a younger demographic. The theme of the collection was ‘The New Eye’ and featured work by artists under thirty, with mine displayed most prominently. My inclusion was not purely a nod to his daughter’s ‘discovery’; I heard through channels that he was under legal scrutiny for having signed appraisals on dozens of auctioned Dali prints that turned out to be forgeries.

In spite of such dealings, I liked Morrie Posner. He was a whimsical, pragmatic man who laughed easily and whose ‘cheer up—it might never happen’ mindset was infectious. His favorite blessing at family meals—to which I was invited regularly, along with Max Simon and Michael—was, ‘They tried to kill us. They failed. Let’s eat.’

That summer, Morrie invited Lauryn and I on the ‘New Eye’ cruise for a meet-and-greet with the passengers, to deliver art enrichment lectures and to introduce me to the liner’s artistic director. I delivered on my end, and at conclusion of the voyage I was awarded a fully-funded residency which would include numerous murals in the corridors, both above and below decks, and would culminate in me painting the ship’s 44,000 square foot hull.

I liked Morrie, and there, on board the Norwegian Spirit, amid alpine mountains, waterfalls and lush villages parading fruit trees, I finally tossed Urban Dictionary out a porthole and conceded that I liked his daughter as well.

By that point I had gotten to know the successful Posner family and had gained tremendous admiration for their relationship to Judaism. So, when I proposed to Lauryn in December, I’d already agreed happily to the few concessions I’d need to make before a rabbi would officiate. I did not have to convert, although one day I might. For the time being, I had to attend classes in the faith and agree that our children would be raised Jewish. My parents were less than pleased with this, and it got so awkward that my brother declined my request to be my best man. Asking him had been a peace offering, and sadly, my other choice—Max Simon—suffered a debilitating stroke in the first part of May. In the end, Lauryn’s brother Daniel stepped in; he’s an amicable and generous attorney for the Innocence Project, and it was an honor to have him at my side.

I did not invite Alyssa to the wedding, but I continued to see her, before it and afterward. It sounds like abysmal behavior, and of course, it is. Lauryn never knew about this, nor wondered where I went on certain nights since I’d maintained my loft in the city.

Years rolled by. Lauryn’s gallery blossomed and I made my mark on the art world. We bought a beautiful Tudor a block from her parents’ house and we created two beautiful little Jewish girls without a trace of Episcopalian about them beyond their Scottish surname. Alyssa and I were of a moment, but Lauryn and I were of a lifetime.

I admit—with genuine chagrin—that I suffered no real angst over my dishonesty. I should have, but mainly because I’ve read fairy tales about how things are supposed to be. Honesty looks great on paper, but there are dagger wounds that are not only mortal but unnecessary. I had sporadic if voracious thirsts, and I was able to keep them in check within the larger framework. I had a single attic door that I kept locked, and I managed to keep the secret so secure that it co-existed in equilibrium with everything else.

For her part, Alyssa shrugged my ring off as inconsequential and remained as accommodating as ever, although she reworked an old joke: “You know the difference between a fucking a Jewish girl and fucking a tonk girl? With a tonk girl, the diamonds are fake but the orgasms are real.”

It was funny, but it wasn’t true. Lauryn and I were beautifully matched, flesh and fire; Mall Guy had spotted it long before either of us. Alyssa was my only bout with infidelity, but it was consistent and unrelenting, and—through its duration, under any convoluted set of excuses—unfair to everyone except me. I told myself that it was compatibility and stopped second guessing it. Alyssa’s scent had drawn me in, and then it drew me back, and for many years, and her scent did not change. Until one day, it did.

A decade had passed since our chance encounter in Diamond Artist Supply. Over the years, I’d learned something of Alyssa’s background; she was guarded about much of it, but when she drank, she chattered. I knew that the blue house in front of the quarry pond had belonged to her grandmother, and then to her mother, and that they’d both died of cancer. Still, it was more of a surprise to me than it was to Alyssa when she called one day and said she’d been diagnosed with malignant tumors in her ovaries.

I was working on a series based on advertising posters from the 1950’s for the Colby College Museum of Art, and I’d been consumed; it had been almost four months since I’d visited Alyssa. Her call that sunny afternoon was perfunctory—she was making them to the few people she believed should know. It was not a matter of great urgency, she insisted—she was thirty-six, and with the treatments she was undergoing, the prognosis was excellent. She’d already had the surgery and several rounds of chemo; she’d stopped drinking and drugs, and was—she said—learning to navigate a world that had lost its Technicolor.

She assured me that Medicare was taking care of the medical bills and that her boss at the restaurant had been a doll about her schedule, but I wrote her a check anyway. Still, she hesitated when I asked if I could see her the next day, and it took a while before understood why. I trusted she knew that it was guilt and shame and a universe removed from desire. I apologized for being so out of pocket and she finally agreed to see me, saying, “No portraits this time, though.”

Soft places tugged me as I realized that her reluctance to see me was vanity; chemo plays hell on the body. I knew that, but when I showed up the next day, I was not prepared for how savagely she’d been wrecked. She wore a slouchy, steel-blue snood over her bald head and a long dress over her shaky limbs. She greeted me with grace and poise, but under the simple dignity was something deeper and more sinister: Profound, distracted emptiness. This I did not attribute to cancer drugs, but to sobriety: Now that her wall of drink had tumbled down, she was fully exposed, and the change in temperament was difficult for me to witness. If she could maintain it, abstinence might become a good thing, but now it produced an outlook that was closer to despair. She was living in one of her paintings: It was the glare of reality and there was no longer a machine you could shove in front of it.